Infilling for development along our coastline has been taking place for more than half a century in many of Nova Scotia’s coastal towns. While this practice may have been sound at one point, that is no longer the case. The results of coastal climate change, including sea-level rise, storm surge, coastal flooding, and increased frequency and intensity of weather events, put structures along our coastline at risk.

For more than a decade, municipal and provincial governments have been creating regulations to mitigate risky development practices and enhance public safety. The creation of artificial land through infilling to extend development out into the ocean is dangerous and damaging to coastal ecosystems. This ill-advised practice puts people and structures at risk, strains our coastal ecosystems, damages fish and fish habitats, and threatens water quality. Yet the practice of infilling for development continues regularly along Halifax Harbour and in the Northwest Arm.

What Are Water Lots?

What Are Water Lots?

Water lots are portions of the seabed that extend outward from the shoreline. The original intent of these water lots was for fishers to build wharves to dock their fishing vessels. Wharf construction is considered a temporary interference on a coastal ecosystem and is far less destructive than infilling and development.

The governance of water lots is complex. The Municipality does not govern them. They are submerged lands or seabeds and, as such, do not fall under municipal land-use bylaw regulation. However, if the water lot is partially or fully infilled, the Municipality is then responsible for governing the use and development of the newly created ‘land’ that results from the infilling activity. Ordinarily, the submerged land in the intertidal zone would fall on the cusp of provincial governance, with potential implications under the Environment Act, the Crown Lands Act, the Beaches Act and the incoming Coastal Protection Act, but the unique ‘water lot’ designation grants private ownership and puts the water lot in an odd governance space between federal jurisdiction and property rights. The federal jurisdiction of this segment of the coastline potentially invokes regulation under the Navigable Waters Act (Transport Canada) and the Fisheries Act (Fisheries and Oceans Canada), both of which have undergone significant changes in recent years. Depending on the location of the infilling, there could also be Species at Risk Act implications.

This odd federal designation of the seabed, with municipal jurisdiction over infilled ‘land’ on a water lot, has left a governance gap or loophole in the system. This means that it takes very little for a property owner to gain approval for an infilling permit, despite the tremendous damage and great risk associated with an infilling project. At this time, there is no provincial assessment of damage or risk associated with water lot infilling, despite the potential impacts under the above-mentioned pieces of provincial legislation. Both the municipal and provincial governments respond to any ‘water lot’ inquiry by pointing out that this is not an issue they have jurisdiction over while confirming that it is environmentally problematic.

In order to receive a permit to infill a water lot on the Halifax Northwest Arm, a property owner must apply to Transport Canada under the guidance of the Navigable Waters Act for a permit to infill. Transport Canada considers whether the infilling will cause problems with navigation of the waters. Water navigability impacts are the only criteria for this assessment and Transport Canada’s mandate does not address environmental impacts or any other risks or damage caused by the infill project. Transport Canada reviews an application and offers a 30-day feedback period for the public to express their concerns, but the parameters of those concerns are restricted to impacts on the navigability of the water.

Additionally, a proponent is required to contact Fisheries and Oceans Canada and request a review of the potential impacts of the infilling project on fish and fish habitats. If the project could result in the death of fish and/or the harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat, the proponent must obtain authorization from Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The authorization includes terms and conditions the proponent must follow to avoid, mitigate, offset, and monitor the impacts to fish and fish habitats resulting from the project. Failure to abide by these terms and conditions may result in fines.

Dartmouth Cove Example

Dartmouth Cove Example

A developer made an application for a permit to fill Dartmouth Cove with pyritic slate and quarry rock from local excavation sites. Besides scale, the nature of the fill is cause for concern. According to the application, 42 per cent of the 99,700m³ of infill material is pyritic slate, one of the dominant rocks of HRM’s surficial geography. It can be harmful to surrounding ecosystems once exposed to oxygen and fresh water, producing sulphuric acid, and must be disposed of in carefully managed sites. It is currently used as infill in the Fairview Cove and South End Terminals as provincially monitored disposal sites. Unfortunately, disposal in saltwater seems to be the best method to prevent the rock from oxidizing and leeching acid into the surrounding environment, but monitoring at private sites has a troubled history.

This proposed infill of 2.7 hectares (13 per cent of the cove) will have a drastic impact on the surrounding properties, community, and ecosystems. There is a lot of silt deposited into the water when any rock is dumped into the ocean – not to mention the centuries of industrial waste at the bottom of the cove stirred up by the falling rocks. This is especially concerning considering that eelgrass, a critical fish habitat, has been identified within the proposed infill site.

Under current municipal land use regulations, and as the HRM councillor for the area has made clear, building and development would not be permitted on the infilled land. It’s unclear why the applications would list that the infill project is for future development on their application.

For more specific information on the active infilling application in Dartmouth Cove, please visit:

Northwest Arm Example

Northwest Arm Example

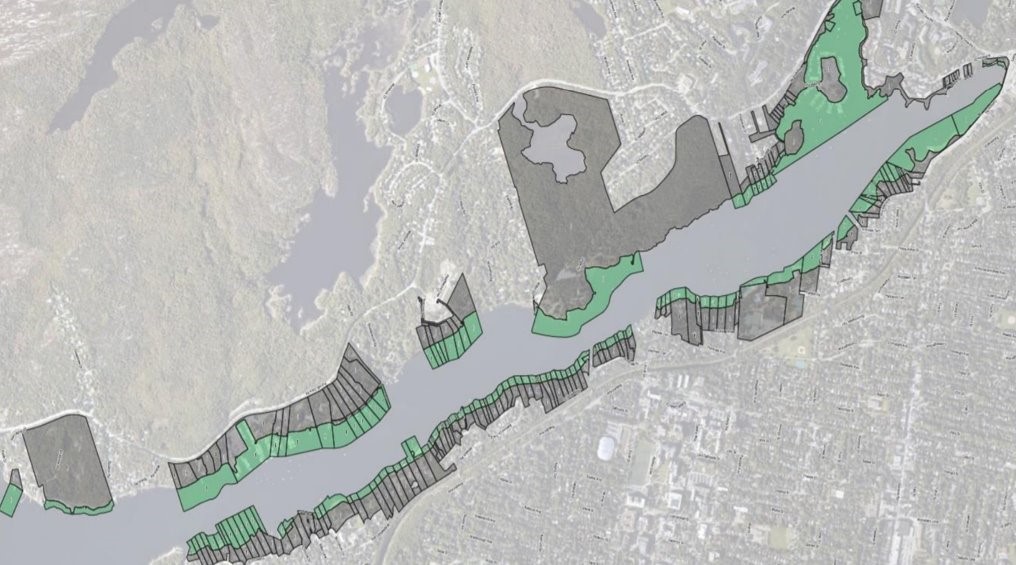

For information on the community campaign and the two active applications in the Northwest Arm, please visit www.protectthenorthwestarm.com. Numerous properties in this area include a ‘water lot’ in the property’s deed. If all lots were infilled, the Northwest Arm would lose 30 per cent of its navigable waters and 50 per cent of its width in some areas, impeding the use of sailing crafts. This map shows water lots lining the Northwest Arm.

History

In the Northwest Arm, infilling water lots for development purposes became an issue the municipality had to address in 2005-2007, with numerous community complaints and media attention. At that time, the Municipality increased its governance over the land (created by infilling) by adding land-use bylaws to restrict the use of the infilled area. These bylaws limited development on the infilled land to boathouses, gazebos, parks, wharves, docks, historical sites and monuments, trails, public works and utilities, and ferry terminal facilities. The height of allowable structures was also restricted. It was set out in these new regulations that the infilled water lot would not change the minimum setback requirements of the previously existing lot, and the infilled water lot would not be included in the calculation of the minimum lot requirements.

Despite the Municipality’s efforts to strengthen the land governance of infilled areas, property owners have continued to infill water lots along the shores of the Northwest Arm. The by-laws have not limited this risky and damaging act. Determined developers have continued to test the boundaries of by-laws. In 2016, a costly, tax-payer funded lawsuit challenged HRM’s governance. A property owner along the Northwest Arm was denied a permit to build a pool due to the setback requirement along the shoreline. The property owner then made an attempt to make his property eligible for the pool by infilling his water lot. When the property owner’s second pool permit request was denied, because the infilling does not change the original shoreline and therefore does not exempt the pool from the required setback, the property owner took the Municipality to court. Thankfully, the lawsuit was unsuccessful. However, this problem has not been resolved and one can logically assume that motivated developers will continue to test the boundaries.

The EAC and community members participated in a federal consultation process managed by the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada in 2022. This brought together stakeholders and representatives from HRM, the Province of Nova Scotia, and Departments of Fisheries and Oceans and Transportation, among other federal political and departmental representatives. HRM and the Department of Transportation are currently communicating to explore a municipal bylaw regulating infilling activities.