In Our Power is a series of stories produced by the Ecology Action Centre of ordinary people and diverse communities in Atlantic Canada working to create a just transition to a green economy. The people in these stories — artists, students, businesspeople, civil servants, activists, people in faith communities and more — have not shied away from the realities of climate change. Instead, they are stepping up to change how we get our energy, and reduce how much we need, while maintaining a world in which people can thrive. We hope you enjoy learning from these communities as they work to switch to renewable and more efficient energy sources — and ensure their communities are strong and resilient.

Follow the Ecology Action Centre on Instagram, Twitter or Facebook to get notified of new posts from In Our Power! Or subscribe to the Culture of Efficiency newsletter.

Recent posts

Introducing The Great Adventure of ESBy the Electric School Bus, an Ecology Action Centre Children's Book

by Aby Lefebvre

The Ecology Action Centre is releasing a kids book!

What if your school bus could help change the future? The Ecology Action Centre is thrilled to announce the release of a brand-new children’s book that brings climate action to life through the story of one small but mighty electric school bus, hoping to change the future.

ESBy Inspires Nova Scotia to Welcome Electric School Buses | Feb. 26, 2026

The Great Adventure of ESBy the Electric School Bus follows the journey of a resilient little electric school bus from British Columbia who travels all the way across Canada to Nova Scotia. Along the way, ESBy meets new friends, overcomes challenges, and shares an important message about clean transportation and climate leadership.

With heart, humour, and determination, ESBy hopes to inspire Nova Scotia to welcome more electric school buses and to show young readers that big change often starts with small, courageous steps. At its core, the story is about friendship, perseverance, and the power we all have to shape a healthier future.

Written by the Ecology Action Centre’s Senior Energy Coordinator, Chris Benjamin, and illustrated by Energy Coordinator Abby Lefebvre, this book was created to help youth connect with environmental issues in a way that feels personal and empowering. By focusing on something many students experience every day, school transportation.

Written by the Ecology Action Centre’s Senior Energy Coordinator, Chris Benjamin, and illustrated by Energy Coordinator Abby Lefebvre, this book was created to help youth connect with environmental issues in a way that feels personal and empowering. By focusing on something many students experience every day, school transportation.

The story opens the door to meaningful conversations about climate action, renewable energy, and community leadership. The book is available free of charge in both English and French. Copies can be picked up at the Ecology Action Centre between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., and will also be available at select community events, including an upcoming book launch.

Stay tuned to our social media channels for launch details and happy reading!

The Housing Construction Council's Training Programs Are Building a Green Transition Workforce

by Chris Benjamin

A few months ago, the EAC Energy & Climate team hosted a Better Building Speaker Series event on the economics of building efficiency, how we need to understand that while building efficiently comes with expenses, the savings and benefits are far, far greater.

One of the speakers was Jessica Ward of the Housing Construction Council of Nova Scotia, who spoke about their Housing Construction Training program, which by the end of this year will have given hands-on home-building training to 80 equity-deserving candidates, people who have struggled but through this program have shown themselves to be capable individuals with excellent contributions to make to the green transition.

They will have completed 13 net-zero houses on the mainland and in Cape Breton. I was so inspired, I had to sit down and interview Jessica for this post. Her work shows that the construction industry can be a home for workers from all backgrounds and situations.

Lived Experience with Barriers Informs Solutions to Training Needs | Jan. 22, 2026

Jessica Ward, HCC

Chris Benjamin: How did these three programs come to be?

Jessica Ward: The sector council participated in developing training with Nova Scotia Community College. We developed an eight-week training program on housing-construction fundamentals. It was skills developed on various construction projects ranging from building picnic tables to finishing walls. It didn't have a full construction piece.

eight-week training program on housing-construction fundamentals. It was skills developed on various construction projects ranging from building picnic tables to finishing walls. It didn't have a full construction piece.

We knew there was a need for training but it wasn’t as successful as it could have been so we went back to the drawing board. That’s when I started working for the Housing Construction Council. And this part of the story gets a bit personal. My son had experienced homelessness for a long time. I was always his main advocate. We reached a point where he could enroll in a program like this. But he had a lot of barriers. He didn't have Grade 12 so he could not have done the micro-credential with NSCC. He had started his GED (high school equivalent) but then it was nationalized and he had to start over. He lived in rural Nova Scotia and did not have access to reliable transportation. He was very representative of folks who are unemployed.

All this lived experience really informed my work. And we took what was helpful from the first program, for example working with partners like NS Works, who are employment experts. We needed more wraparound supports. We needed to provide proper tools because many learners don't have any. We worked with a red seal instructor and they needed more support in teaching, especially for learners with learning disabilities.

We put all the pieces together and built out a curriculum. Then in 2024, the Province allowed development of micro-credential with post-secondary and industry working together. But we partnered with secondary schools, regional centres for education, and Cape Breton University, which had experience in micro-credentials in net-zero and affordable housing with the Nova Scotia Nonprofit Housing Association. All three organizations partnered on curriculum.

And we met with industry to ensure we met their needs. They identified gaps in learning, sometimes how to swing a hammer, or properly install windows, energy efficiency and net-zero knowledge. Passive house knowledge. Keeping up with new building codes. We updated the curriculum with the 2020 building codes.  All that led to our Annapolis Valley pilot project from September 2024 to June 2025. My son was one of our first graduates. He was chosen to be in the program, but they didn’t know we were related. He’s been working in construction ever since. He may want to become a heavy-machinery operator.

All that led to our Annapolis Valley pilot project from September 2024 to June 2025. My son was one of our first graduates. He was chosen to be in the program, but they didn’t know we were related. He’s been working in construction ever since. He may want to become a heavy-machinery operator.

You could insert any person with barriers. It helped that I had lived experience with his challenges: lack of rural transportation, accessing income assistance. needing warm clothes for the job site. Understanding that the privileges some of us have don’t exist across the board. Everybody in our programs gets boots and warm clothes.

CB: What have been the outcome?

JW: We trained 24 individuals from September to June, in three cohorts. Nineteen graduated. All 19 went to work or onto college.

They built three net-zero energy ready homes last year. This year we are running three curricula concurrently, in Cape Breton, King’s County and Annapolis County.

We’ll have trained 80 people by year end, completing 13 houses. Our goal is 280 trained by next year in all seven regional centres of education. We're getting the pieces in place. We have to get the school boards in. a red seal to cover the area, which involves travel within a 100-130 km radius. We have to be enough services available for wrap around supports. We can’t do it on our own. The status quo wasn’t going to work with the housing need right now.

CB: Who lives in the homes?

JW: In Cape Breton, the units are part of New Dawn’s affordable housing portfolio. We have six 2-bedrooms in Lawrencetown. We partnered with the Rotary, ensuring they go to those in particular need of homes, who don’t have the means. We have three1-bedroooms that will be affordable housing in Kentville, Coldbrook and Lawrencetown. We are partnering with nonprofit housing providers. It's based on needs of individuals.

partnered with the Rotary, ensuring they go to those in particular need of homes, who don’t have the means. We have three1-bedroooms that will be affordable housing in Kentville, Coldbrook and Lawrencetown. We are partnering with nonprofit housing providers. It's based on needs of individuals.

CB: What energy-efficiency features are included?

JW: Heat pumps, HRV systems. We do a double wall for insulation, almost a foot thick. High efficiency hot water heaters. Energy efficient appliances. Rooftop solar to make them net zero energy ready. Triple pane windows. Fibreglass doors. And we work with Passive Design Solutions to maximize efficiency. Efficiency Nova Scotia’s New Home Research Project has been a big help.

CB: What would you tell business owners about all this?

JW: Come out and see it for yourselves. We do an open house midway through the project. Employers can see the work being done. It’s like a living resume.

They can watch learners doing the mudding on drywall, installing windows. We have asked industry and included what they tell us they need. We have multiple safety certifications in the program, life confined spaces and asbestos awareness training, fall arrest training for roofers. Learners use scaffolding every day. They use pneumatic, power, and hand tools.

All but two weeks of the program is learning by doing. They learn by making mistakes. They are learning what’s new in energy efficiency. While not becoming red seals, they learn about all levels of the trades, good work habits and why these things matter, The whys and hows.

We've trained all kinds of works. From age 16 to 59 have participated. We've worked with actively homeless people. People from shelters. People who were in prison. People just getting off parole. We'll soon have someone on a day pass while incarcerated. People with disabilities. LGBTQ+, African Nova Scotians, Indigenous particpants. We have women red seals and men red seals as trainers. And we're getting a lot more women participating: 4 of 10 in the current Cape Breton program.

Construction can work for anyone and we want to show it. Our apprentices want to work with any red seal who will give them a chance.

CB: Thank you for your great work and sharing your story with us.

JW: My pleasure.

Efficiency = Affordability

by Hannah Minzloff

Do you struggle to pay your utility bills? Are you living in a drafty home? Want to do something about climate change?

These are the questions Juli Bishwokarma and I asked during our November rural libraries workshop tour. We met with people in the community to talk about tips on home energy efficiency for renters and home owners, review the most effective order in which to undertake energy efficiency retrofits, and share information about Efficiency Nova Scotia’s excellent rebate programs. We also presentede information about ways we can all take action to support EAC’s proposed solutions to reducing our energy bills and lifting people up out of Energy Poverty.

Home Energy Efficiency--Our Part for the Planet | Dec. 3, 2025

My absolute favourite part of community workshops is the time spent in conversation with the public! I love hearing people’s personal stories about their old drafty homes, a new solar EV panel installation, the way a home's previous owner built cool features into the home like a way to collect rainwater for indoor use, or the time they found seaweed insulation in their walls.

My absolute favourite part of community workshops is the time spent in conversation with the public! I love hearing people’s personal stories about their old drafty homes, a new solar EV panel installation, the way a home's previous owner built cool features into the home like a way to collect rainwater for indoor use, or the time they found seaweed insulation in their walls.

I urge you to consider doing what you can to make your home more energy efficient. Efficiency Nova Scotia is there to support you every step of the way. Your home will be more comfortable, it will be healthier, and your energy bills will go down. And you can feel great that collectively as Nova Scotians we're moving the whole province closer to reaching our targeted greenhouse gas reduction targets—doing our part for the planet.

One participant shared that the workshop was "life changing" literally. I'm so grateful for the Efficiency Energy & Affordability program."

Photo credits: Juli Bishwokarma

Halifax takes part in Draw the Line

by Badia Nehme

On Sep. 20, 2025 activists, organizers and organizations of all ages and sectors came together to tell the government that it was time to draw the line against putting profit over people, Ignoring Indigenous voices and sovereignty, fueling the war machine, alienating and devaluing migrant workers and immigrants and perpetuating climate change.

An International Day of Global Action and Resistance | Oct. 23, 2025

This was an opportunity to bring people together to learn and advocate for a just future. The event lasted from 1 - 4 p.m. at Grande Parade in Halifax.

Organizations and activists had the option of setting up a booth with information and calls to action. Seniors for Climate had rock for climate rocking chairs, the Workers Action Centre had sock puppets for activism, several petitions were tabled, the Ecology Action Centre had eco-trivia as well as post cards for Prime Minister Carney where you could demand a just climate future.

Organizations and activists had the option of setting up a booth with information and calls to action. Seniors for Climate had rock for climate rocking chairs, the Workers Action Centre had sock puppets for activism, several petitions were tabled, the Ecology Action Centre had eco-trivia as well as post cards for Prime Minister Carney where you could demand a just climate future.

It was not just a day of learning it was also a day filled with calls to action through music and speeches. Melissa Marsman, secretary treasurer from the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour, highlighted Nova Scotia’s energy growing affordability crisis:

“Right now we see workers putting in long hours and sometimes working two or three jobs and still not making enough to pay rent. We see people on social assistance scrape by on rates that don’t even cover basic needs, and we see students leaving school buried in debt. We also see seniors choosing between paying for their prescriptions or paying their power bill. Meanwhile corporations brag about record profits and handing out millions to executives, while families line up at food banks! That is not a coincidence that is an economy designed to reward greed over need! And we say no more!”

This was not the only call for change. Dr. El Jones recited poems highlighting the iolence of genocide, its impact on humanity and the people of Palestine. It is time for Canada to stop funding war and genocide! Violet Paul, a Knowledge Keeper with Sipekne’katik First Nation brought this conflict closer to home by highlighting Canada’s history of genocide and the current treatment of Indigenous peoples, directly challenging Prime Minister Carney’s Building Canada Act, which seeks to bypass checks and balances including Indigenous consultation for the sake of “nation building” that would only benefit corporations.

This was not the only call for change. Dr. El Jones recited poems highlighting the iolence of genocide, its impact on humanity and the people of Palestine. It is time for Canada to stop funding war and genocide! Violet Paul, a Knowledge Keeper with Sipekne’katik First Nation brought this conflict closer to home by highlighting Canada’s history of genocide and the current treatment of Indigenous peoples, directly challenging Prime Minister Carney’s Building Canada Act, which seeks to bypass checks and balances including Indigenous consultation for the sake of “nation building” that would only benefit corporations.

Stacey Gomez from the Centre of Migrant Workers Rights highlighted the mistreatment and exploitation of migrant workers; their labour is essential to Canada and it is time they are granted immigration status and granted far more protections then they currently experience.

I had the privilege of speaking for the EAC and highlighted the connection between people and the environment. We need to listen to the traditional and rightful stewards of the land and follow the voices of Indigenous peoples. We should not forsake our health and environment for corporate greed and the exploitation of workers. I highlighted how war fuels climate change and that the exploitation of migrant workers is deeply integrated into our agricultural production. We need to create a localized, sustainable food system.

Nova Scotians, Canadians, and people around the world deserve better from their governments. They need governments that serve the people and not the rich few. We need to demand governments and a society that prioritize people, listen to Indigenous communities respecting sovereignty, stops the proliferation of war, recognizes the status of migrant workers and newcomers and protects our environment.

It is time we draw the line, here and now, and demand better!

A Day of Fleet Electrification

by Abby Lefebvre

We were thrilled to host “A Day of Electrification” this August, a successful event dedicated to promoting and sharing knowledge about electric school bus adoption. Held in the vibrant and engaging setting of Steele Wheels Motor Museum, the event brought together leaders, innovators, and stakeholders from across the electrification industry.

We're Excited for the Day Nova Scotia Finally Adds Electric School Buses to Its Fleet | Sept. 25, 2025

Guests heard from International (IC Bus), a trusted name in student transportation since the early 2000s. In 2020, IC Bus launched its line of electric school buses, built specifically for Canadian roads and climates. Known industry wide for its impressive braking system, the IC electric school bus is already making waves in British Columbia, where it first hit the road.

Guests heard from International (IC Bus), a trusted name in student transportation since the early 2000s. In 2020, IC Bus launched its line of electric school buses, built specifically for Canadian roads and climates. Known industry wide for its impressive braking system, the IC electric school bus is already making waves in British Columbia, where it first hit the road.

We also welcomed Rush, a transportation company at the forefront of fleet electrification. We learned about their work on electric-

bus software, charging-battery infrastructure, and cutting-edge technologies like Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G), which enables electric buses to feed energy back into the power grid when plugged in. The event wrapped up with a ride along in an IC electric bus, followed by great food and time to connect with others driving change in the sector.

It was an absolute pleasure to host IC Bus, Rush, Western Canada Bus, and many passionate stakeholders for this inspiring day of learning. We look forward to the day when Nova Scotia joins the rest of Canada in adding electric school buses to its fleet.

How Worried are YOU About Climate Change?

by Kate Brooks

Worldwide surveys tell us the vast majority of us ARE very concerned about climate change—but many of us stop short of taking action on climate in our daily lives. Here in the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM), a series of public engagements indicated that about 40 percent of adults don’t know how to get involved or don’t feel their actions will make a difference.

Increasingly, people say they’re worried about cost-of-living issues like food, housing, and energy prices. People aren’t connecting the dots between climate change and rising costs.

Every Single Action Matters | Aug 20, 2025

This inaction is a major problem. In HRM, we know that almost 50 percent of the carbon-emission reductions we must make in order to meet our HalifACT climate goals come from individual residents’ choices—how we travel, how we use energy at home, what we eat, etc. Globally, we are now at the point where every fraction of a degree of warming we can avoid is critical. every single action matters.

EAC has been working with HalifACT—HRM’s climate change team—to help residents see themselves in the climate movement. The Climate Commitment Badge Program is one tool we’re developing. It works a bit like Scouts, where you earn a badge for learning new skills and taking action.

Right now, there are three badges: Climate 101, Home Energy, and Getting Around. Additional badges (Food, Nature, and Community Resilience) will be launched this fall.

Right now, there are three badges: Climate 101, Home Energy, and Getting Around. Additional badges (Food, Nature, and Community Resilience) will be launched this fall.

When you commit to signing up on the program website and taking as many actions as you can, you receive a badge—a beautiful lapel pin designed by local artists.

So, what are these actions? Our definition of “climate action” is broad and includes steps that can help us reduce carbon emissions, prepare for and adapt to the effects of climate change, build resilient communities, and think differently about how we relate to living systems. Instead of a list of “shoulds,” we’ve carefully curated content to inspire you to find YOUR best action. Everyone has differing capacities to act and that’s okay.

The content aims to connect you to local opportunities for volunteering and interaction, and includes many actions that can save you money, improve your health, and strengthen your community. You’ll find videos, podcasts, readings, audio clips, quizzes, and more!

save you money, improve your health, and strengthen your community. You’ll find videos, podcasts, readings, audio clips, quizzes, and more!

The bottom line is this: While our individual actions are not enough to eliminate climate change, our actions DO matter, and many of the steps we can take will improve our quality of life and capacity for resilience. Finding YOUR place in the climate conversation means contributing your unique skills and abilities. While we can’t all do everything, we can all do something!

If you or your community group would like to know more about the Climate Commitment Badge Program, please reach out! I’m happy to visit groups of all kinds and can offer informal conversations, formal presentations, or whatever your organization needs to get the climate conversation going.

Email Kate at kate.brooks@ecologyaction.ca.

Teens for Climate will Empower the Next Generation

by Lauren Furlong

Teens for Climate is an exciting new initiative launched by the Ecology Action Centre (EAC), designed to empower high school students in Nova Scotia (grades 9-12) to take meaningful action on climate change. This program provides a dedicated space where youth can engage in open discussions, collaborate with peers, and work on environmental projects that directly address the climate challenges facing our communities.

Youth Will be at the Heart of the Action | Aug 20, 2025

At Teens for Climate, young voices aren’t just heard—they’re at the heart of the action. The group focuses on building real, actionable plans with the support of EAC staff, turning ideas into tangible solutions.

At Teens for Climate, young voices aren’t just heard—they’re at the heart of the action. The group focuses on building real, actionable plans with the support of EAC staff, turning ideas into tangible solutions.

Over the course of the year, participants will have the chance to work on long-term projects, attend skill-building workshops, and join monthly online meetings that keep them connected to the growing youth climate movement. Whether you’re passionate about environmental justice, sustainability, or climate advocacy, Teens for Climate offers a dynamic, inclusive environment where Nova Scotia’s youth can make a real difference.

With support from EAC’s experienced team, these young leaders will gain the tools and knowledge to drive lasting change in their communities and beyond.

The Atlantic Faithful Footprints Roadshow

by Shreetee Appadu

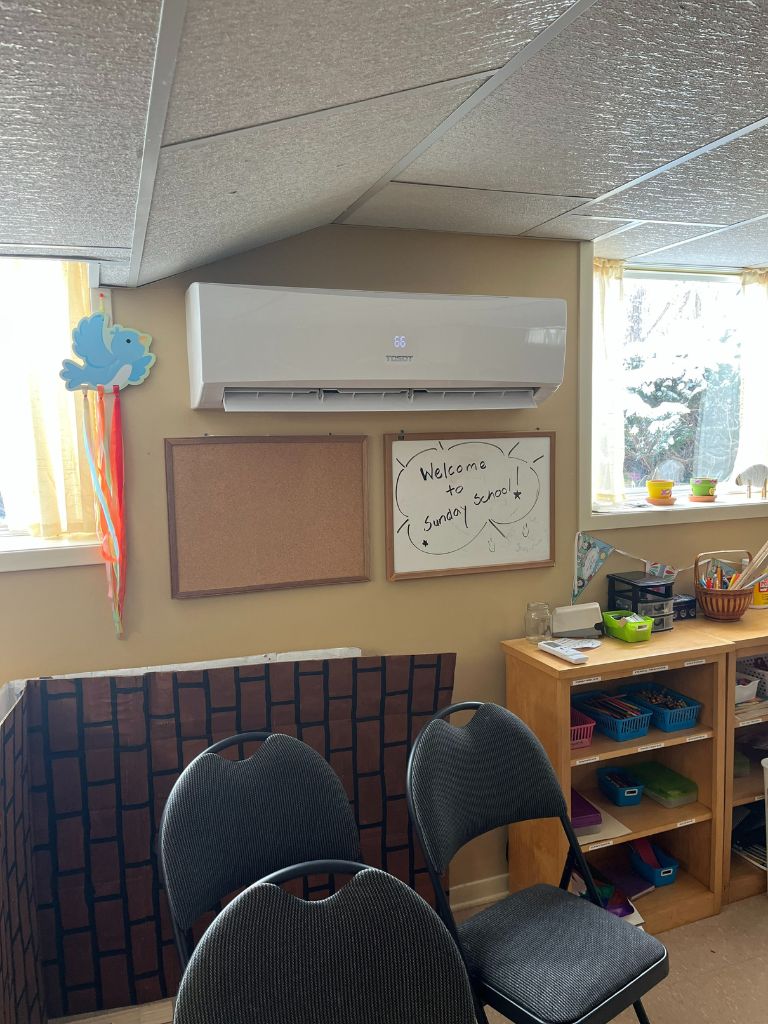

During the months of March, April and May, I went around to the four Atlantic Provinces to connect with United Church congregations who had retrofitted their buildings for energy efficiency using the Faithful Footprints Program of Faith & the Common Good. The Faithful Footprints Atlantic Roadshow was organized to celebrate the congregations who have successfully who have successfully retrofitted their buildings using the grant and encourage connections between congregations.

Roadshow highlighted successful retrofits and increased community connections | July 24, 2025

Through the Faithful Footprint Atlantic Roadshow, I wanted to connect with as many United Churches as possible. I organized six stops around the Maritimes: Carman United-Cape Breton, Central United Lunenburg, and Grace United in Dartmouth; Sackville United in New Brunswick; and Hilcrest United Montague and Spring Park United Charlottetown in Prince Edward Island.

The Roadshow participants were all looking forward to sharing their stories of using the grant and encouraging others to follow in their footsteps. All the participants mentioned not only the environmental benefits but also the social and economic benefits that they experienced after doing an energy retrofit. In a true celebratory fashion, many of the events were opened with a choir singing hymns about taking care of the Earth, along with tea and snacks provided.

The Roadshow participants were all looking forward to sharing their stories of using the grant and encouraging others to follow in their footsteps. All the participants mentioned not only the environmental benefits but also the social and economic benefits that they experienced after doing an energy retrofit. In a true celebratory fashion, many of the events were opened with a choir singing hymns about taking care of the Earth, along with tea and snacks provided.

At my first stop in Carman United, the event started with the choir, after which we had Paula Francis and Daniel Mckeough share the retrofit journey of the congregation. Along with them, we also had Marc Stone and Sherry Baccardax from St Peter’s United, who shared their story. Sherry came prepared with a 1-page document of all the resources she used to get the work done, which was very useful for the attendees to have access to.

Then I headed to Sackville in New Brunswick where I was welcomed by Minister Lloyd and Catherine Gaw, who shared that the retrofits not only helped them save money but also increased environmental awareness among the members. My next stop was Hillcrest United in Montague in Prince Edward Island, where I met Melissa Mullen and the Green Team who spearheaded the projects and have reduced their oil use by half, saving thousands of dollars since the retrofit.

helped them save money but also increased environmental awareness among the members. My next stop was Hillcrest United in Montague in Prince Edward Island, where I met Melissa Mullen and the Green Team who spearheaded the projects and have reduced their oil use by half, saving thousands of dollars since the retrofit.

Next stop was Spring Park United in Charlottetown, where I attended the service that happened to be on Palm Sunday. I was warmly welcomed by all and along with Kathy Bigsby and Steven Dickie we celebrated the great work done at Spring Park United. On the same day we headed to Park Royal United to do a building tour which connected the 2 congregations even more.

The next event was hosted at Central United in Lunenburg during Earth Week 2025 which is organized by The United Church. This is a week where their communities of faith, networks, and regions are encouraged to participate in climate justice events and to pray, learn, and act for the love of Creation. Collin and Shelley Mann who led the retrofits talked about their journey and challenges in installing 19 Heat pumps in an 1,885 year-old church which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The work was not easy but as the Minister shared: “This project that we've undertaken here at Central United is a big part of how we are being a bold and daring, justice-seeking church together.”

The next event was hosted at Central United in Lunenburg during Earth Week 2025 which is organized by The United Church. This is a week where their communities of faith, networks, and regions are encouraged to participate in climate justice events and to pray, learn, and act for the love of Creation. Collin and Shelley Mann who led the retrofits talked about their journey and challenges in installing 19 Heat pumps in an 1,885 year-old church which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The work was not easy but as the Minister shared: “This project that we've undertaken here at Central United is a big part of how we are being a bold and daring, justice-seeking church together.”

I wrapped up the Roadshow at Grace United in Dartmouth, where we also commemorated the legacy of Robert Picco, who led the energy retrofits in the church and has since passed. It was truly wonderful to connect with so many congregations and witness their dedication in reducing their carbon emissions, working toward a greener future. From the participants to the attendees, so many stories were shared and being able to engage over tea and coffee reinforced the relationships between members.

Many of the attendees left the events with hopes and reassurance that they too could take on such projects. Although doing an energy retrofit is not an easy task, especially for a group who mostly volunteers their time, many United Churches have shown us that it is possible. Here’s to more retrofitted faith buildings and a greener future.

Building Better Through Social Enterprise

by Hannah Minzloff

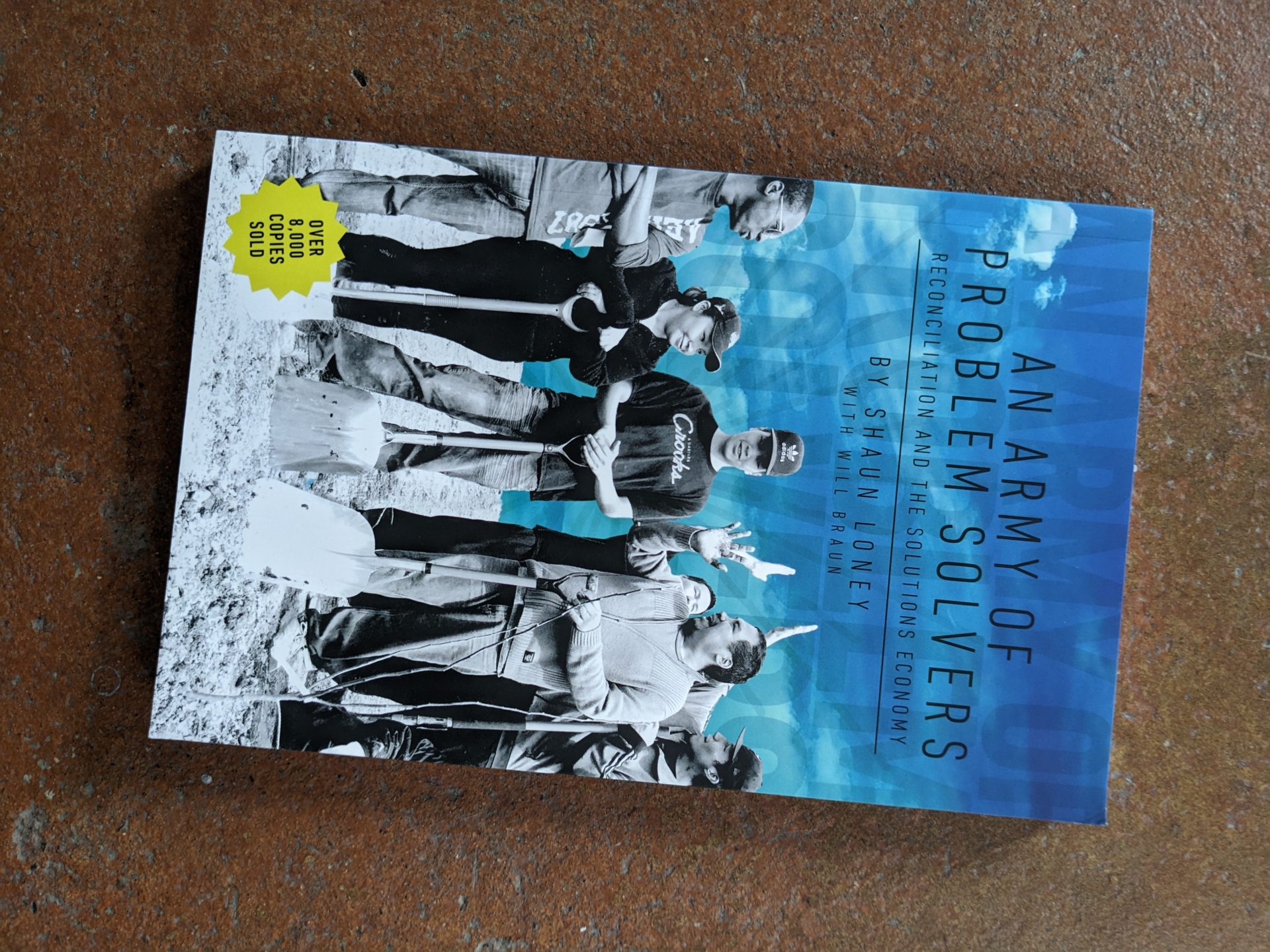

I first heard about Shaun Loney through his book An Army of Problem Solvers: Reconciliation and the Solutions Economy. I’m generally a fast reader, but this book took me months to get through because I had to keep pausing to take notes, to look things up, and to take time to reflect on what I had learned, and how it could be applied to my work at Ecology Action Centre.

“The only thing that will work is different” | June 26, 2025

Shaun is a Manitoba-based author and social entrepreneur with a strong track record of creating energy transition and employment in First Nations communities. He has co-founded and mentored over a dozen successful social enterprises including BUILD Inc and AKI Energy. In the early 2000s Shaun was director of Energy Policy for the Government of Manitoba. Shaun believes in connecting the people who most need the work with the work that most needs to be done.

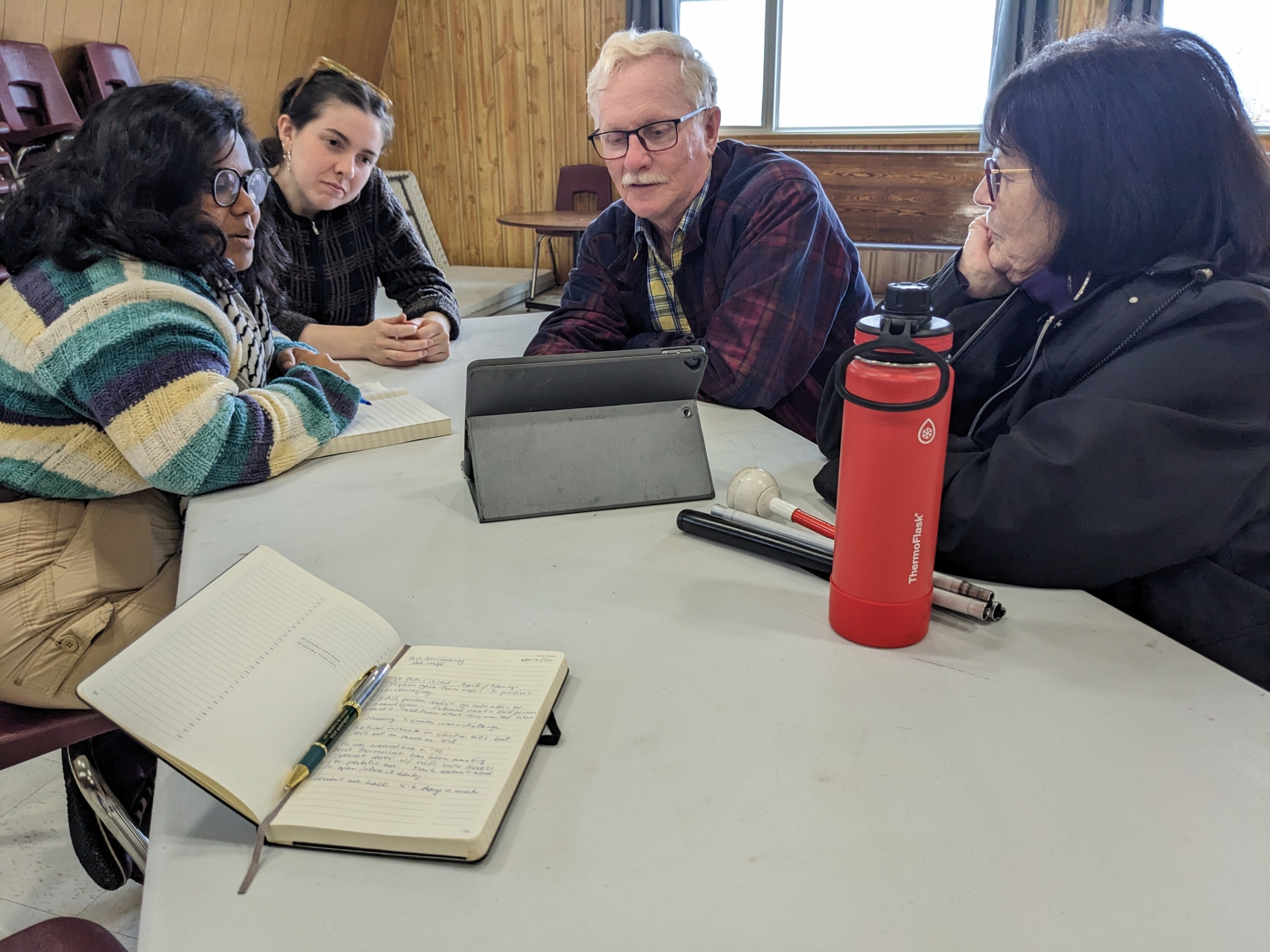

This year, our Better Building Speaker Series moved from a virtual platform to in-person. As our first guest of the year, we invited Shaun to come to Nova Scotia to lead a week of engaging workshops and rich conversations.

Shaun’s message is clear: “The only thing that will work is different”.

He asked tough questions: “What is the value of what we're doing? What would happen if we stopped doing this work for a few days, weeks, months, a year?”.

He shared important and surprising facts: Nonprofits are competing with each other for money; Non-profits are subsidizing government; Our solutions save government money; Government is the financial beneficiary of the work we are doing.

We met with the Province’s Clean Buildings staff, the Nova Scotia Native Council, an Indigenous Energy Efficiency start-up, hosted the Building Better in Nova Scotia green jobs report launch, and spent two full days at the Eltuek Arts Centre in Sydney. There we listened and brainstormed with over 40 people about how social enterprise could play a significant role in alleviating energy poverty, while creating opportunities for people to access green jobs training in Unama’ki/Cape Breton, through initiatives like neighbourhood retrofits.

the Building Better in Nova Scotia green jobs report launch, and spent two full days at the Eltuek Arts Centre in Sydney. There we listened and brainstormed with over 40 people about how social enterprise could play a significant role in alleviating energy poverty, while creating opportunities for people to access green jobs training in Unama’ki/Cape Breton, through initiatives like neighbourhood retrofits.

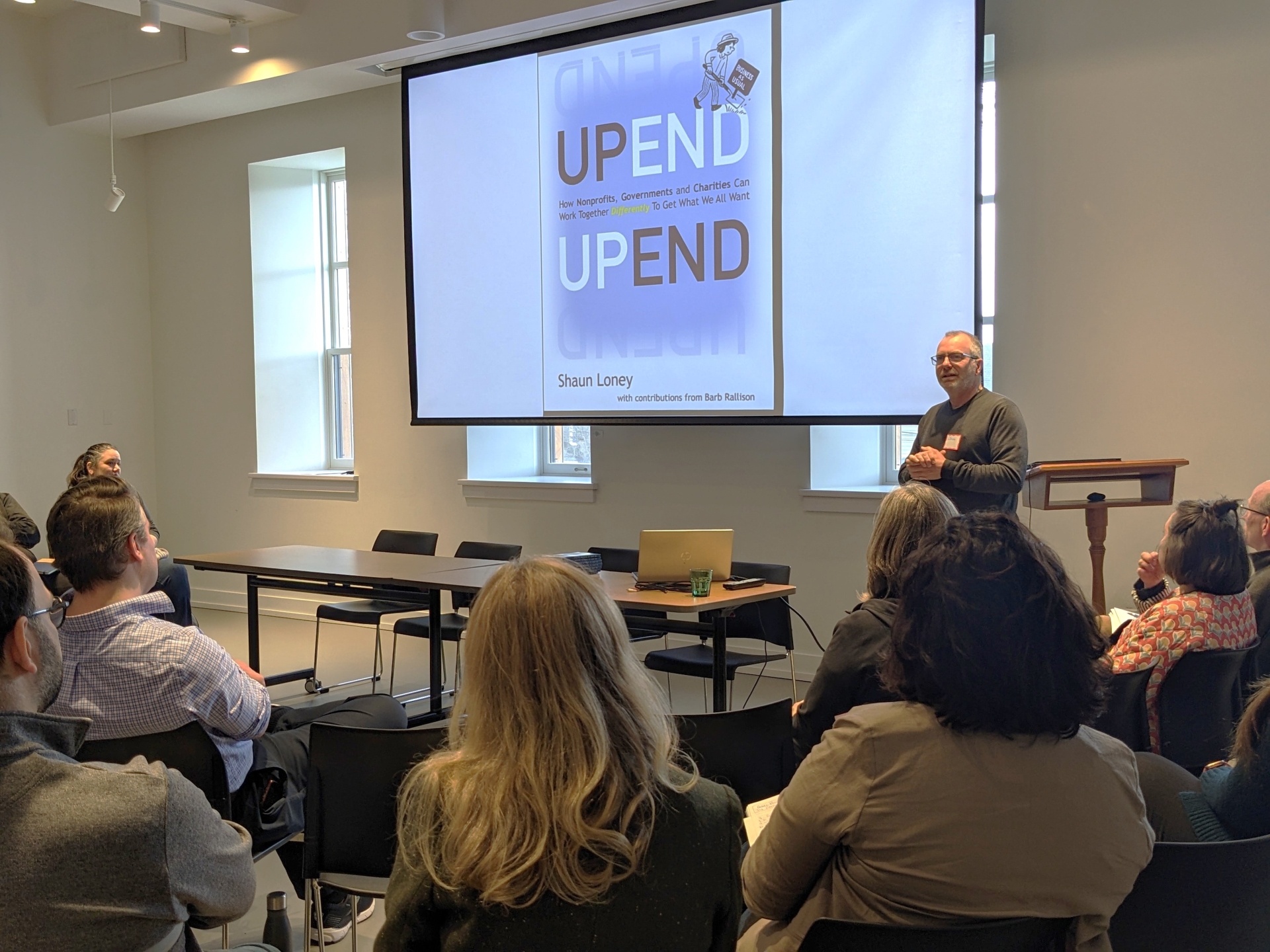

Shaun's new book UPEND, to be released in the coming months, is a toolkit outlining how to make this approach work. Shaun says, “UPEND is the practitioner’s essential guide to unlocking resources for social good. Finally, a practical path to making meaningful progress on addressing homelessness, poverty, crime and climate change.”

Shaun's new book UPEND, to be released in the coming months, is a toolkit outlining how to make this approach work. Shaun says, “UPEND is the practitioner’s essential guide to unlocking resources for social good. Finally, a practical path to making meaningful progress on addressing homelessness, poverty, crime and climate change.”

Let’s get cracking and connect the people who most need the work with the work that most needs to be done.

Building Nova Scotia's Green Workforce

by Chris Benjamin

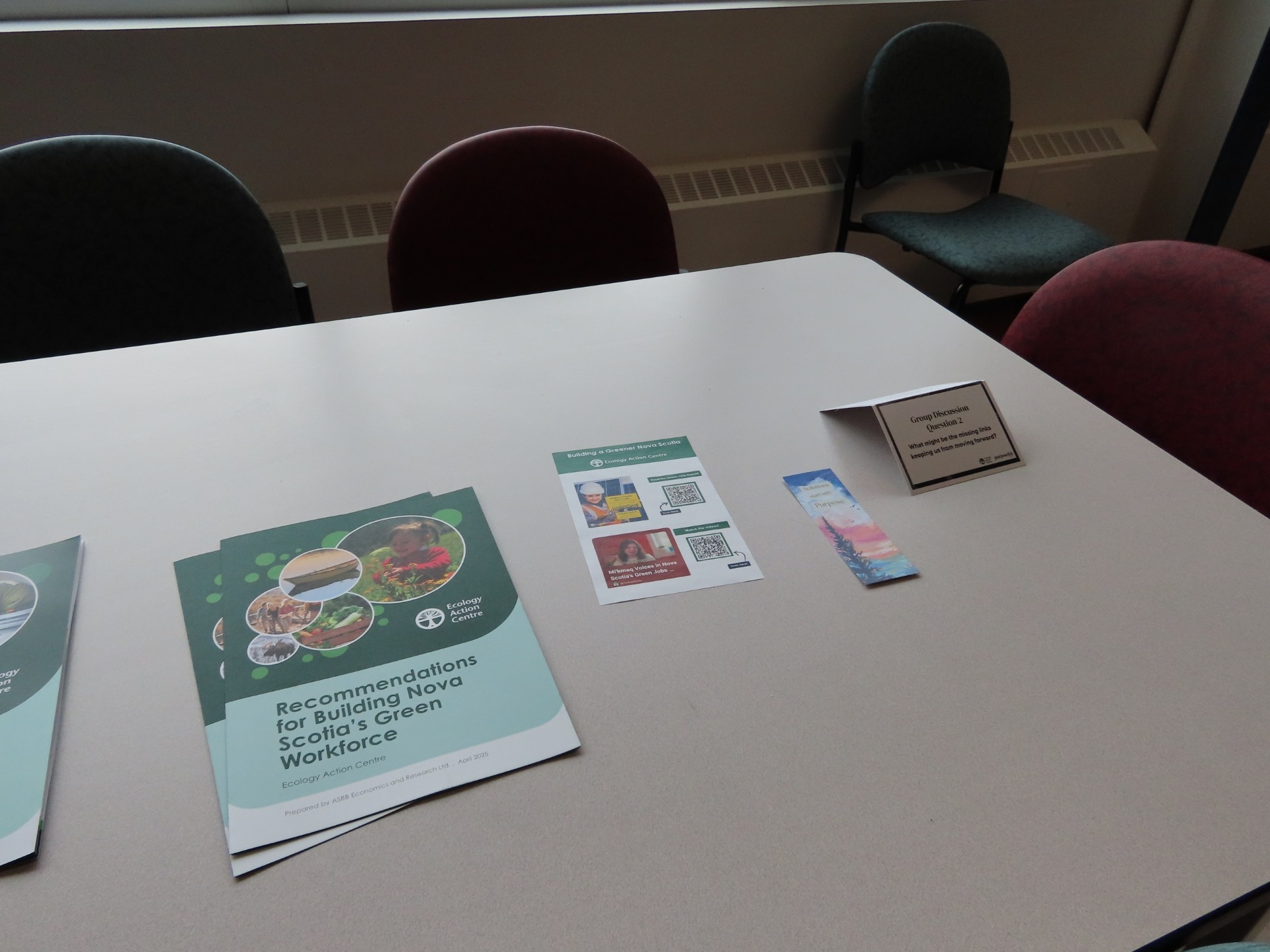

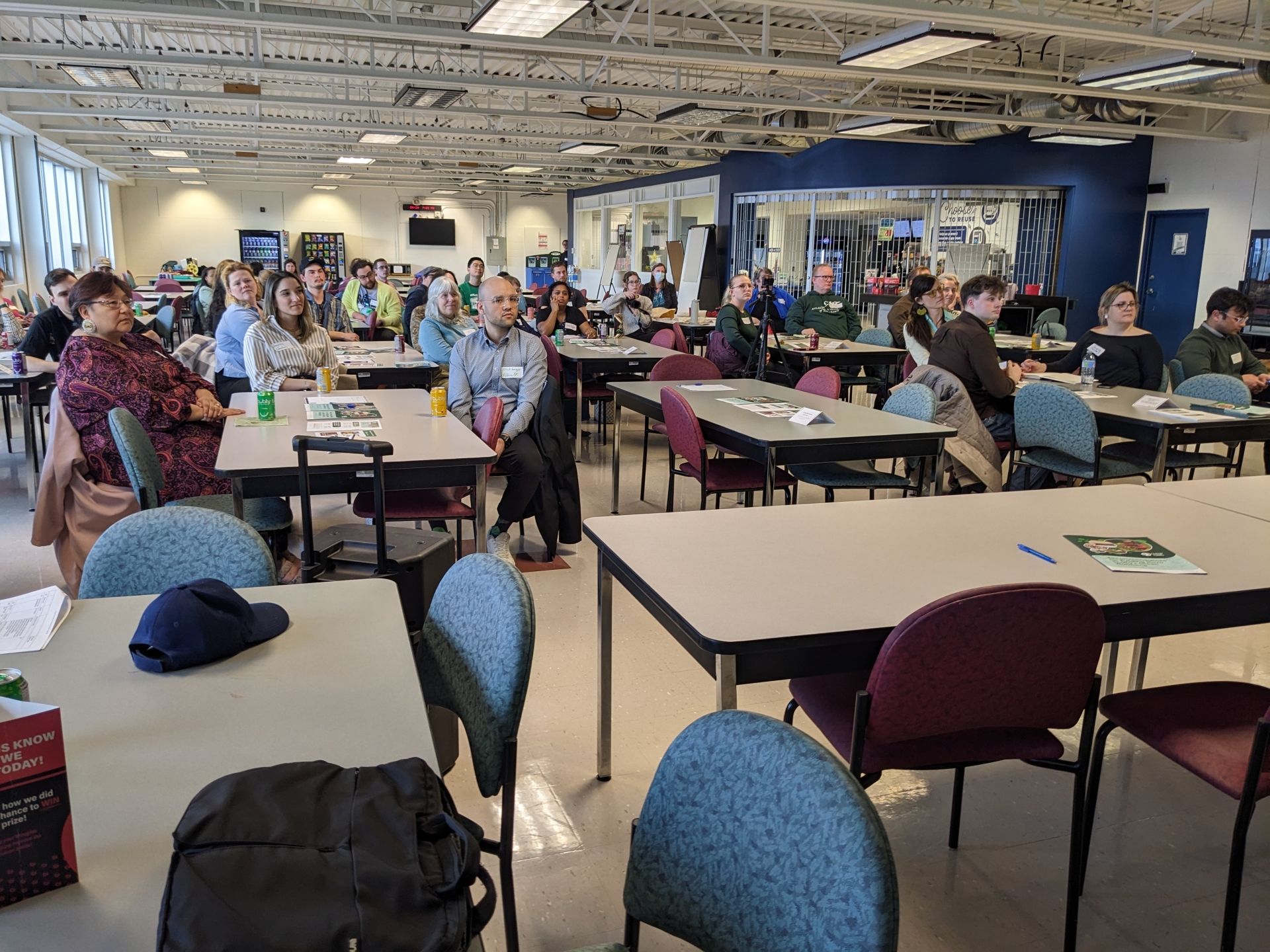

Ecology Action Centre recently released Building Nova Scotia’s Green Workforce: Addressing Labour Gaps for a Net-Zero Future to a crowded house at Nova Scotia Community College's IT Campus in Halifax. The detailed report looks at building retrofits, which are crucial in reaching greenhouse gas reduction targets. Within this area of energy efficiency, the report identifies which jobs will see the most growth, as well as barriers faced by workers entering the sector.

Remove Barriers for BIPOC, disabled, and gender-diverse workers | May 22, 2025

Speakers included Mani Chakrabarty of ASBB Consulting, lead author of the report, Montanna Labradore of Glooscap Ventures, and Social Entrepreneur and Author Shaun Loney.

We launched a new video called Mi'kmaq Voices in Nova Scotia's Green Jobs Sector, available below, about Montanna and other Mi'kmaw workers in the green economy, from the trades to governance to project management.

Chakrabarty provided context and detail of the report, its methods and recommendations. Loney inspired with stories of his work in Manitoba founding social enterprises to train Indigenous workers in trades that benefit their own communities, providing better housing and long-term employment security. As Loney says, "it's not outside the box, it's inside the circle."

Chakrabarty provided context and detail of the report, its methods and recommendations. Loney inspired with stories of his work in Manitoba founding social enterprises to train Indigenous workers in trades that benefit their own communities, providing better housing and long-term employment security. As Loney says, "it's not outside the box, it's inside the circle."

After a rigorous Q&A session, Purposeful Group's Lisa Lowthers facilitated a small group session where attendees including civil servants, NGO employees, union members, students, and others discussed the report and how to apply its lessons, what changes are already happening, and how to overcomer barriers to change. Participants found that green jobs can address the inequities of climate change impacts and help communities become self-sustaining, while coping with, adapting to or remediating the consequences of a changing climate. These jobs are invaluable in the fight against the climate and biodiversity crises, and can be the building blocks of a vibrant, sustainable economic future for Nova Scotia.

What I Learned from the Donkin Mine Community

by Juli Bishwokarma

When I moved to Nova Scotia, I knew little about coal, not just its physical makeup or its emissions profile, but its history here, its reach, and how it continues to shape everyday lives. While working on our Advancing Clean Energy Transitions project, I found myself wanting to dig deeper, what does it really mean to live near a coal mine? That’s when I met Catherine Fergusson, co-founder of Power Beyond Coal and a core member of the Cow Bay Environmental Coalition.

Two Thousand Days of Noise | April 24, 2025

Catherine’s advocacy is deeply personal. She lives it. Together with her partner Michael, they’ve been amplifying the stories of their community, particularly in Port Morien, a small seaside village just a stone’s throw from the Donkin coal mine.

Michael built gobsmack.org as a living archive of community voices and resistance. Reading through it was like peeling back layers of frustration, hope, and a relentless desire for dignity and justice.

Here’s what I learned.

Port Morien has a problem, one that’s invisible, constant, and corrosive. For over two thousand days, residents have endured the industrial hum of methane ventilation fans from the Donkin Mine. That’s not background noise; it’s a health and quality-of-life issue. It disrupts sleep, causes anxiety, and steals away the peace of coastal living.

The mine, operated by Kameron Coal (a subsidiary of The Cline Group), reopened in September 2022 after being on pause due to safety concerns. But this wasn’t a fresh start, the mine wasn’t sealed during its closure in 2020. Methane still needed to be ventilated, so the fans kept running. The community kept suffering.

An Unjust Process

The environmental assessment process that allowed Donkin Mine to reopen didn’t even address the noise problem. Let that sink in. The system that’s supposed to protect public health ignored one of the most pervasive harms. Meanwhile, Port Morien residents, many older, many with deep ties to this land, are left to cope with a degraded environment, eroded trust, and no real avenue for repair.

The environmental assessment process that allowed Donkin Mine to reopen didn’t even address the noise problem. Let that sink in. The system that’s supposed to protect public health ignored one of the most pervasive harms. Meanwhile, Port Morien residents, many older, many with deep ties to this land, are left to cope with a degraded environment, eroded trust, and no real avenue for repair.

Catherine and others in the Cow Bay Environmental Coalition have stepped in where the government has stepped back. They’ve written reports, built community support, and fought for truth, the kind that acknowledges the real cost of fossil fuel extraction on human lives.

What We Urge

If we want a just and sustainable future, we must stop sacrificing communities like Port Morien. Here’s what we’re calling for:

-

Stop the noise. It’s unnecessary, harmful, and preventable. Hold Kameron Coal accountable and stop the ventilation noise.

-

Strengthen environmental assessments. Our regulatory systems need a serious upgrade, especially when it comes to tonal noise and its health impacts. Honest, community-informed assessments should be the standard, not the exception.

-

Move away from coal and emissions-heavy sources. Coal is not the future. It’s time for Nova Scotia to turn the page and invest in clean, community-owned renewable energy.

-

Invest in people. Port Morien deserves reparations, mental health support, public infrastructure for well-being, and resources to help the community recover and thrive.

-

Empower communities. Local groups like Power Beyond Coal and Cow Bay Environmental Coalition are doing the work. Decision-makers need to listen, partner, and fund community-led solutions, not undermine them.

-

Retrain and transition workers. Let’s support miners with real opportunities, certification programs, green jobs, and secure livelihoods that don’t cost their health or the planet.

-

Honour the treaties. Extracting fossil fuels on Mi’kma’ki dishonors the Peace and Friendship Treaties. We are all treaty people. Our actions and our energy decisions must reflect that responsibility.

-

No more sacrifice zones. Fossil fuels are toxic not just to the environment, but to people. The land and people of Cape Breton have given enough. It’s time to stop asking them to give more.

Meeting Catherine reminded me that advocacy isn’t abstract. It’s lived. And listening to communities like Port Morien, I realized: the coal industry doesn’t just extract resources. It extracts trust, health, and peace of mind.

Unless we stand up and say enough. Let’s stop the noise, literally and figuratively. Let’s imagine a future where the energy we use doesn’t come at someone else’s expense. And let’s build it together.

If you want to learn more or support the movement, visit gobsmack.org, follow Power Beyond Coal, or reach out to local environmental organizations standing in solidarity with Port Morien.

Taking Back the Power

by Badia Nehme

On Wednesday March 5, roughly 500 people took to the streets in front of Province House for the “Special Interests” for Democracy rally with a unified voice that said: “The Houston government does not have a right to alter the democratic process.” The rally was prompted after a series of bills that sought to undermine public engagement, government checks and balances, and municipal and academic voices.

Energy Sovereignty, Democracy Highlight “Special Interests” for Democracy Rally | Mar 27, 2025

Speakers fired up the crowd calling for government accountability, solidarity with the working class, standing up against corporations, greed, and environmental degradation.

One notable call to action was from Mi’kmaq Activist Cheryl Maloney. She called for the restructuring of our energy and resources. To put them into the hands of the people to reclaim it form Nova Scotia Power.

“The solution isn’t with governments and corporations. It’s with human beings,” Maloney said. This is a crucial call going forward in the fight against climate change.

As Nova Scotia decarbonizes, energy democracy and community energy are pathways to clean, stable, and affordable energy. Energy democracy means giving people and community the right and ability to chose where their energy comes from. Community energy means energy owned by the community, and used for the community.

Energy democracy was a clear call to action in the face of Bill 6, An Act Respecting Agriculture, Energy, and Natural Resources. As the omnibus bill seeks to lift the bans on fracking and uranium exploration, many sight the fact that the bill ignores the years of public engagement and Indigenous consultation; the results of which oversaw hundreds of responses and thousands of attendees with 91% of respondents being in favour of the ban.

“We spent years deciding together to ban fracking and now he says he has to have an adult conversation about reversing extraction," said Robin Tress of the Council of Canadians

Nova Scotian’s having the right to a ban is not bad policy. The ban is the result of the clear voice of the public will and years of research. The right to choose where our energy comes from is about fostering a strong and prosperous renewable energy future.

A combination of energy democracy and community energy is the most proactive route to creating this green future. Nova Scotians use 29% less energy than the national average, yet we face some of the highest energy bills and rates of energy poverty.

Energy co-operatives, municipally owned utilities, and community-choice aggregated communities have all provided clear energy grids that are stable, a source of community economic development, and demonstrate lower rates than large power corporations. It is something we should be demanding from our governments, while continuing to stand against the face of resource extraction.

From Gas to Green: A Family’s Journey to Sustainability

by Juli Bishwokarma

When Chris Caputo, a chemist by training, and his wife decided to make a change five years ago, they didn’t expect it to transform their lives so profoundly. What started with swapping out their gas-powered car for an electric vehicle (EV) in mid-2019 has since turned into a full-scale effort to eliminate fossil fuels from their home.

Now parents to two young children, Chris and his wife are passionate about creating a sustainable future—one step at a time.

The Journey to Being an Earth Hero | Feb 27, 2025

For Chris, sustainability has always been more than a buzzword. “As a chemist, I’ve been trained to think about impact and efficiency,” he explains. “Living sustainably feels like a natural extension of who I am. But more importantly, it’s about setting an example for my kids and doing our part to ensure they have a livable future.”

This ethos inspired the family to take bold steps to reduce their household’s environmental footprint. The motivation went beyond environmental stewardship. By tracking emissions using apps like Earth Hero, Chris gamified the process, using data to better understand their household’s impact.

“It’s kind of fun to plug in your info and see how you compare to average emissions,” he says. “It keeps you motivated and grounded in what really matters.”

The First Step: An Electric Vehicle

The journey began with their decision to purchase an electric vehicle, or EV. Though they missed out on the Ontario provincial EV rebate, which had been discontinued, they took advantage of the $5,000 federal rebate to offset costs.

“Switching from a Hyundai Accent that cost $200 a month in gas to a car that costs $20 a month to charge was an easy decision,” Chris recalls. To accommodate the EV, they installed a 240-volt outlet outside their house and later upgraded their home’s electrical system to support more energy-efficient appliances.

“Switching from a Hyundai Accent that cost $200 a month in gas to a car that costs $20 a month to charge was an easy decision,” Chris recalls. To accommodate the EV, they installed a 240-volt outlet outside their house and later upgraded their home’s electrical system to support more energy-efficient appliances.

"Chris credits a growing charging network across the country for making the transition relatively seamless. "You plug in your destination and the car tells you where the charging stations are - it's effortless. That made adopting the technology so much easier"

Retrofitting Their Home: One Change at a Time

Over the years, the family worked systematically to replace their gas appliances with electric alternatives. They got rid of their gas furnace, stove, and water heater, leaving only the propane BBQ as a final holdout. To finance some of these changes, they tapped into the Canada Greener Homes program, which offers interest-free loans for energy-efficient upgrades like heat pumps and tankless water heaters.

“We didn’t do it all at once,” Chris emphasizes. “We replaced appliances as they aged, prioritizing the oldest and least efficient ones first. It’s a process, but it’s worth it. Our electricity costs have actually gone down despite adding new appliances because everything is so much more efficient.”

Surprises and Benefits Along the Way

The transition has brought unexpected benefits beyond financial savings. “We used to spend $60 to $140 a month on gas, and now our gas bill is basically $10 for the BBQ,” Chris explains.

“Our electricity costs average $150 a month, which is lower than before we made the switch. But the biggest surprise has been the air quality in our home—it’s so much better now that there’s no gas.”

Their EV has also transformed how they think about transportation. “The maintenance is minimal, there’s no wear and tear, and the acceleration is so smooth. I could never go back to a gas-powered car,” Chris says.

Advice for Others Considering the Switch

Chris acknowledges that the upfront costs of retrofits and EVs can be a barrier, but he encourages others to start small. “You don’t

have to do everything at once," he says.

"Start by replacing your oldest appliances or consider active transportation for short distance errands. I know switching to an EV isn't possible in every city in Canada, but I'd also like to stress that you don't necessarily even need an EV.

"Active transportation or public transit are equally important alternatives. Also, look into programs like the Canada Greener Homes—they offer great support for home efficiency.”

Ian's Story: A Journey to Energy Efficiency and Sustainability

by Juli Bishwokarma

Ian Mallov had always envisioned a future where his lifestyle aligned with his values. When he and his partner moved to Halifax, it marked the beginning of a new chapter.

Though the transition came with challenges, such as adapting to limited public transportation options compared to their previous home in Toronto, it also presented an opportunity. Ian decided it was time to act on a long-held goal: to buy an electric vehicle (EV).

For Ian, this was more than a practical choice—it was a step toward a sustainable future.

Why an Electric Vehicle? | Jan 23, 2025

Ian’s interest in EVs wasn’t new. Growing up in a progressive household, he had been exposed to discussions about clean technology and sustainability from an early age. By the time he began considering a car, he had already ruled out gas-powered vehicles.

“It just didn’t make sense to invest in something that goes against my values,” he says. He saw EVs as a way to reduce his family’s carbon footprint while contributing to a broader shift away from fossil fuels.

“I’m really passionate about sustainability and the need to tackle climate change. It’s such an urgent issue. I know individual actions alone won’t solve everything, but they do add up and can help drive bigger changes.”

The Decision-Making Process

The journey to owning an EV wasn’t simple. Ian spent months saving and researching.

Financial obstacles were a major hurdle, but he was encouraged by the availability of a used EV rebate, which significantly reduced costs. Ian also benefited from federal and provincial government rebates, though he believes there should be more financial support available to make EV ownership accessible to a wider audience.

Ian consulted with a friend in Toronto who owns a Tesla and connected with another acquaintance in Bedford for guidance. As a scientist by training, Ian values direct conversations over online research, finding them more effective than theoretical calculations.

“I talked to so many people before making the decision,” Ian says. “Hearing firsthand experiences made a huge difference, especially when it came to understanding things like range and charging logistics.”

When Ian came across a 2017 Chevy Bolt, he knew he had found the right car. Its battery condition, range, and affordability aligned with his family’s needs. For Ian, buying an EV wasn’t just about practicality; it was an emotional decision rooted in his commitment to sustainability.

Life with an EV

Owning an EV brought noticeable changes to Ian’s life. He enjoyed the consistent pricing of electricity compared to fluctuating gas prices and appreciated the quiet, smooth ride of the Chevy Bolt. However, life with an EV wasn’t without its hurdles.

Ian’s apartment in Halifax lacked the infrastructure for home charging. Efforts to install a private charger were thwarted by space limitations and landlord restrictions. This meant relying on public chargers, which required planning and flexibility.

Apps like ChargePoint and FLO became essential tools for locating available charging stations. Ian found it frustrating that some places, like IKEA, had space for only eight chargers, and grocery stores in Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) often lacked chargers altogether. Progress was being made, but there were still no Level 2 chargers at roadside or fast-food locations, and the nearest fast charger was a 6–7-minute drive away.

Road trips presented their own challenges. “At first, it was overwhelming,” Ian admits. “You have to think about where to stop, how long to charge, and whether the station will even be working.”

Despite these difficulties, Ian found ways to adapt, incorporating overnight charging into his travel plans to minimize reliance on fast chargers.

Takeaways and Advice

Reflecting on his experience, Ian emphasizes the importance of preparation. “Do your research,” he says. “Look into incentives, understand the charging situation in your area, and talk to people who’ve already made the switch.”

He highlights the importance of considering lifecycle emissions, the availability and location of chargers, and electricity-pricing structures, noting that many chargers charge per time instead of per kilowatt-hour.

Ian also advocates for better public charging infrastructure, particularly for renters and apartment dwellers. He stresses the need for incentives or legislation to ensure new buildings include EV infrastructure and for more chargers in underground or street parking.

Ian highlights the critical need for additional rebates, despite the support already available. “The federal government and provincial rebates are a great start, but more needs to be done to make EV ownership possible for everyone, not just those who can already afford it.”

For Ian, the journey to owning an EV was about more than convenience or cost savings. It was about making a choice that aligned with his values and setting an example for his child.

“I know EVs aren’t perfect,” he says. “But they’re a step in the right direction. And sometimes, taking that first step is the most important part.”

Useful resources:

-

Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles (iZEV) Program (Currently paused): https://tc.canada.ca/en/road-transportation/innovative-technologies/zero-emission-vehicles/incentives-zero-emission-vehicles/program-resources-dealerships?utm_campaign=tc-zev-hub-ongoing&utm_medium=doormat-link&utm_source=zev-hub-incentives-page-en&utm_content=izev-program

-

Electrify Nova Scotia Rebate Program: https://evassist.ca/rebates/residents/

-

Multi-Unit EV Charger Rebates: https://www.efficiencyns.ca/programs-rebates/ev-charging-for-multi-unit-residential-buildings

-

Electric Vehicle Association of Atlantic Canada: https://evaac.ca/ , Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/EVAssocAtlCan/

Goin’ Down the Cape Breton Road: United Church edition

by Shreetee Appadu

Last month, the EAC energy team went down the road in Cape Breton to connect with some United Churches who took part in the Faithful Footprints Program. The Faithful Footprints Program is a unique grant program offered by the United Church of Canada, which offers up to $30,000 as grants to its communities of faith to reduce their energy and carbon footprints. The program has been running for several years and remains committed to the goal of reducing the United Church's carbon emissions by 2030.

The Atlantic provinces are home to many United Churches – 700 to be exact. That is just over 25 percent of all United Churches in Canada. On our Cape Breton road trip, we met with members of three different churches, namely St Peter’s United in St Peter’s, Carman United in Sydney Mines, and St John’s United in Big Bras D’Or, to hear a bit about their Faithful Footprints journeys.

Energy Retrofits Resurrecting Church Life and Community | Dec 10, 2024

We started our road trip by meeting Marc and Nancy from St Peter’s United in their newly renovated hall. Marc, who is the chair of Saint Peter’s Grand River, Loch Lomond Unified Board was eager to share their energy retrofit journey with us. From installing new rain gutters and new windows to heat pumps, the church hall was given a new life. They are now able to rent out the hall for other community activities like yoga and dance classes without having to worry about turning on the oil furnace.

We started our road trip by meeting Marc and Nancy from St Peter’s United in their newly renovated hall. Marc, who is the chair of Saint Peter’s Grand River, Loch Lomond Unified Board was eager to share their energy retrofit journey with us. From installing new rain gutters and new windows to heat pumps, the church hall was given a new life. They are now able to rent out the hall for other community activities like yoga and dance classes without having to worry about turning on the oil furnace.

“The hall was a drain on us but now we are breaking even, and the new programmable smart NEST thermostat is helping with keeping the heat on.”

As we continued on our trip, we met with Daniel from Carman United Church in Sydney Mines. Daniel, the treasurer, came ready with the numbers. The installation of heat pumps has helped them reduce their heating costs by more than 50%. Similar to St Peter’s, they are now able to do a lot more activities in the hall than before and more people stay and socialize in the hall after the church service.

The installation of heat pumps has helped them reduce their heating costs by more than 50%. Similar to St Peter’s, they are now able to do a lot more activities in the hall than before and more people stay and socialize in the hall after the church service.

“People are warm and comfortable inside the church which makes them stay behind and socialize more after the service.”

You can read more about the amazing work that Carman United Church did in one of our previous blog posts.

The last church we went to on our trip was St John’s United located on Old Route 5 in Big Bras D’Or. The church is nestled between trees and a fire hall for neighbors. We met with Cynthia who is the chair of the board and was involved with the energy work done by the church in 2021. They have installed new energy efficient windows, removed the oil furnace and installed a central heat pump system which has significantly reduced their oil bill and kept the church doors open.

The last church we went to on our trip was St John’s United located on Old Route 5 in Big Bras D’Or. The church is nestled between trees and a fire hall for neighbors. We met with Cynthia who is the chair of the board and was involved with the energy work done by the church in 2021. They have installed new energy efficient windows, removed the oil furnace and installed a central heat pump system which has significantly reduced their oil bill and kept the church doors open.

“We would never have been able to keep the church open if we still had to pay the oil bill.”

Completing the work was not easy, especially being in a rural area, but Cynthia mentioned that since most of the work was done during the pandemic, that helped with securing contractors. Now post-covid, they can give the church space for free to a line dancing group and the church volunteers do not have to go in person to turn the heat on

The three churches all share the sentiment of hope and revival after being able to complete the energy efficiency and decarbonization work. Although getting the work done has had its challenges, having a strong building committee and a strong sense of community helped with staying focused on the work as well as the support received from the Faithful Footprints team. Moreover, with heat pumps in churches, the congregation members are also inquiring about heat pumps for their own homes, which showcases the importance of faith communities in pushing for environmental change. Participating in the Faithful Footprints program is not only good for the environment but also helps in reviving the church as community spaces.

Affordable Energy Coalition Logs On!

by Kat Turner

Active for nearly 21 years, the Affordable Energy Coalition brings together anti-poverty advocates committed to ensuring universal access to electricity, eradicating energy poverty, and ensuring that the interests of low- and modest-income Nova Scotians are represented in energy issues. A comfortable home is a human right, which includes electricity, heating, and cooling!

Ecology Action Centre is a proud member of this coalition, working alongside direct-service agencies and anti-poverty organizations.

Visit the new website at www.affordableenergycoalition.ca.

A Living History and a Very Useful Tool | Nov 18, 2024

The coalition has been steadfast in advocating for low-income energy efficiency programs, including Efficiency Nova Scotia’s Affordable Multifamily Housing and HomeWarming programs, as well as the Province of Nova Scotia’s Heating Assistance Rebate Program, or HARP. These support low-to-moderate-income Nova Scotians to help keep their power bills down, while keeping homes at a comfortable temperature. This reduces the likelihood that people will be forced to make impossible choices between necessities like food, medicine, and paying to keep their home livable.

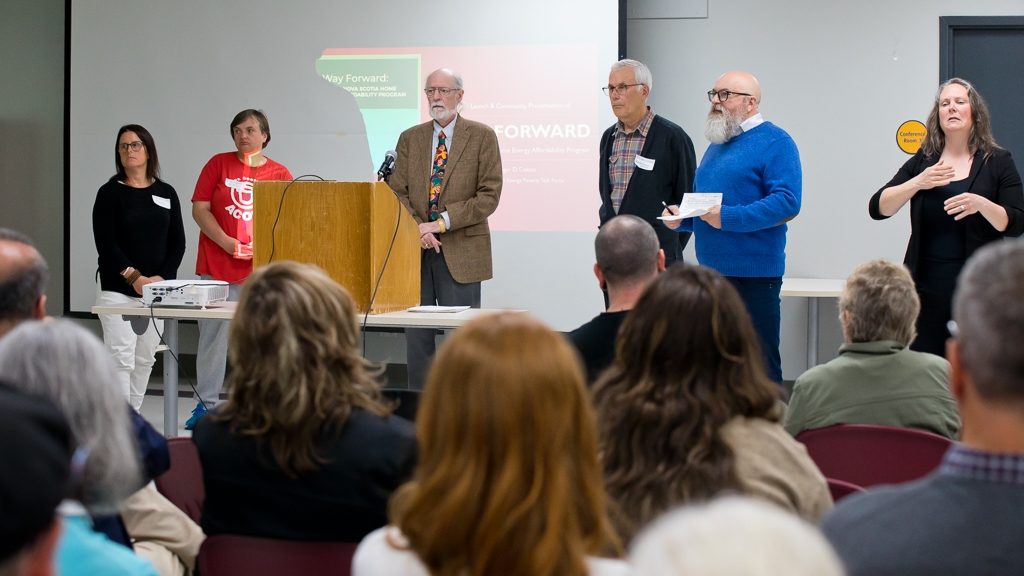

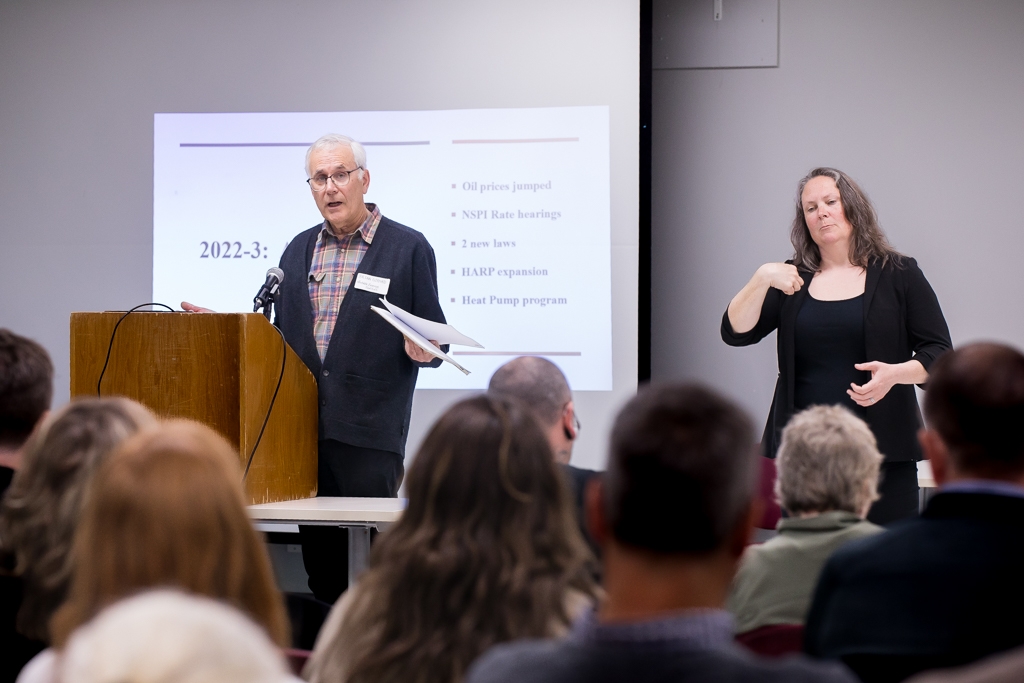

Most recently, the coalition pushed for the creation of the Energy Poverty Task Force, led by then chair Brian Gifford. This taskforce produced the seminal report A Way Forward: A Made-in-Nova Scotia Home Energy Affordability Program, written by energy poverty expert Roger Colton. This report recommends a Universal Service Program that includes on-bill supports, managing late bill payments, crisis intervention, and improved efficiency programming. This work builds on the recommendation the coalition has been making for nearly twenty years.

With more than two decades of social, legal, and political advocacy taking place “behind the scenes”, the Affordable Energy Coalition is beyond excited to have a new platform to share its work with the public. The brand-new website will serve as a living history of the coalitions’ work and be a helpful resource and directory for similar work being done across Turtle Island.

With more than two decades of social, legal, and political advocacy taking place “behind the scenes”, the Affordable Energy Coalition is beyond excited to have a new platform to share its work with the public. The brand-new website will serve as a living history of the coalitions’ work and be a helpful resource and directory for similar work being done across Turtle Island.

More than anything, we hope this new platform will invite more connection with other individuals and communities in the same fight, and spread our message of affordable, accessible, and reliable energy for all!

Zooming into Health: Electric School Buses for Children’s and Drivers' Health

by Abby Lefebvre

n July, I had the privilege of attending a fascinating D250 presentation on school bus safety, in beautiful Penticton, BC (that's me in the photo!). D250 sets the standards for school bus safety at both the provincial and federal levels.

After hearing about various safety features, such as stop arms, seat sizes, aisle dimensions, and reflectors, I began to wonder why we weren’t addressing the safety of children’s lungs and the inhalation of chemicals from fuel bus emissions.

This realization launched the idea to create a report and host an event in Halifax to raise awareness about the impact of school bus emissions on children's health.

We Wrote a Report, Created a Toolkit and Hosted an Event! | Oct 17, 2024

Over the summer, The Ecology Action Centre, New Brunswick Lung, and the Conservation Council of New Brunswick gathered reports, scientific findings, and Canadian statistics. And we monitored air quality inside a school bus.

We compiled all this information into a 12-page report for parents, teachers, bus drivers, students and concerned community members, highlighting the numerous physical and mental effects that school bus emissions have on children’s health and the health of drivers. To accompany the report, we created a toolkit to help individuals learn more about electric school buses, their functionality, cost savings, and other benefits. The toolkit also includes resources for advocating for mandated adoption of electric school buses in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland, following the lead of our counterparts in Prince Edward Island.

We compiled all this information into a 12-page report for parents, teachers, bus drivers, students and concerned community members, highlighting the numerous physical and mental effects that school bus emissions have on children’s health and the health of drivers. To accompany the report, we created a toolkit to help individuals learn more about electric school buses, their functionality, cost savings, and other benefits. The toolkit also includes resources for advocating for mandated adoption of electric school buses in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland, following the lead of our counterparts in Prince Edward Island.

To launch the report and gather support, we hosted an event on October 6th at NSCC’s Ivany Campus in Dartmouth. The event featured a Lion Electric School Bus, Electric Vehicle Test Rides from Next Ride, exhibitor booths from collaborating organizations, and presentations from health and environmental professionals.

Cathy Cervin, a retired family doctor and Dalhousie professor representing the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment Nova Scotia, discussed how these emissions affect our health. She was followed by Melanie Langille from New Brunswick Lung, who spoke about lung health and the impact of emission pollutants.

these emissions affect our health. She was followed by Melanie Langille from New Brunswick Lung, who spoke about lung health and the impact of emission pollutants.

The final presentation was by Autumn Downey from the Conservation Council of New Brunswick, who addressed how electric buses can contribute to healthier, happier communities. Following the presentations, we held a panel discussion to allow for questions.

While parents listened to our expert presenters, youth had the opportunity to engage with a presentation about electric school buses. The kids learned about the sources of carbon emissions, their effects on the environment, and how electric school buses can help mitigate these issues.

It was a pleasure to host everyone and to hear fantastic questions from community members. The report and toolkit can be found on the EAC website under the ‘Reports and Resources’ tab. Click here to find a recording of the event.

Meaningful Action at the Neighbourhood Level

by Scott Osmond

It is easy to be overwhelmed by the climate crisis and to feel that the actions of an individual cannot make a difference. But sometimes it only takes the actions of one person to enact big change in their community.

Fifteen years ago, longstanding climate activist Ruth Gamberg did just this when she took on a neighbourhood-based project to see what she and her neighbours could do to address their impacts on the local environment. In doing so she set an example of something we can all do in our daily lives to make a difference, while also demonstrating the importance and power of coming together as a community to create change.

Togetherness is Power | Sept 26, 2024

“I contacted a number of neighbours,” Gamberg recalls, “and asked if they were interested in getting together to talk about things we could do in our daily lives that would have a positive effect on the environment.” They began by watching a shortened version of Al Gore’s film, An Inconvenient Truth. Gore’s passionate and personal approach to the film, intermixed with the predicted catastrophic effects of doing nothing, inspired them to take a more critical look at their own lives and how they could take action.

With the discussion that followed, Gamberg and her neighbours came up with a list of ideas to try. Some action items included:

Water Conservation: Doing laundry in cold water, installing low-flow showerheads, and watering their gardens more efficiently with soaker hoses, only during the evening hours.

Energy Efficiency: Transitioning to energy-efficient lighting such as LED light bulbs, turning off lights and appliances when not in use, and using a clothesline or indoor rack instead of a power-consuming dryer. They learned more about home energy audits and scheduled a tour of the Ecology Action Centre’s Fern Lane Office for inspiration.

Going Solar: Exploring the potential of solar panels for sustainable energy generation.

Transportation: Opting to walk or carpool, avoid unnecessary idling, and practice fuel-efficient driving methods such as maintaining proper tire pressure and lowering speeds on highways.

Waste Reduction: Recycling and composting where possible, buying in bulk, and using reusable bags. Using old newspapers as wrapping paper.

Join or Volunteer with an Environmental Organization

Share These Ideas with Your Kids!

After their first successful meeting, the group decided to meet monthly and discuss new ideas and challenges and share their achievements. This built a new sense of community.

This neighbourhood collaboration introduced the group to new ideas, concepts, and information, and allowed members to share useful books, films, and

organizations. As a unified group, they were also able to invite local experts and professionals to join their meetings and share the work being done around the community.

At one meeting, a representative from the Halifax Municipal Environmental Services Group provided information on the city’s waste management, and insights into best practices to follow. “They gave us useful information about sorting compostables, recyclables and trash,” says Gamberg.

The group grew with time. Gamberg says many of her neighbours adopted new sustainable practices, which they integrated into their lives. Families were able to teach their children valuable lessons in environmental awareness and sustainable practices, instilling these lessons in the next generation.

The group grew with time. Gamberg says many of her neighbours adopted new sustainable practices, which they integrated into their lives. Families were able to teach their children valuable lessons in environmental awareness and sustainable practices, instilling these lessons in the next generation.

“It was not uncommon for neighbours, those who had showed up for meetings as well as some others, to informally discuss their new habits, other related ideas, materials to read, how their kids would remind them to turn off the lights,” Gamberg says.

It is not uncommon to sometimes feel helpless in addressing the climate crisis, but as with the case of Ruth Gamberg’s neighbourhood project, collective action can have a large and meaningful impact on our communities. Gamberg’s initiative to simply bring people together in a collective space demonstrates the importance of even small actions on building stronger and more resilient communities.

My Experience with Energy Affordability and Efficiency

by Carleigh MacKenzie

I grew up in a household that overconsumed, didn’t sort garbage, and denied the climate crisis.

I remember asking for reusable and sustainable items on my Christmas lists. I was vegan for three years, then vegetarian. I shop at small markets and choose sustainable options when I can. I thought this was what it meant to be environmentally aware until I began working in this field.

I researched legal barriers and remedies to energy efficiency in affordable housing | Aug 20, 2024

In October 2023, I became a research assistant for disaster response and climate planning. I fell in love with environmental law and policy, environmental justice, climate disasters, and adaptation.

My internship with Ecology Action Centre has opened this world up for me. At the beginning of my internship, the only thing I knew was that I would be working with the Energy Team. I had no clue what that meant and only had a slight idea of the project I would be working on.

My experience with energy affordability and efficiency is limited but personal. While I grew up in a household that was not environmentally aware, we also could not afford power bills and gas. Power became not only a financial drain but also a limitation on housing. I knew I wanted to work in the environmental space but learning about energy efficiency and affordable housing appealed to those personal experiences.

During my time with the Energy Team, I researched legal barriers and remedies to energy efficiency in affordable housing. I learned that a landlord looking to receive rebates through Efficiency Nova Scotia’s Affordable Multifamily Housing Program must agree to a 12-year term charging only the maximum rents set in the agreement.

They must pass this covenant to the next owner if they decide to sell the property or lose the rebate. This protects the tenant but is a barrier for landlords.

They must pass this covenant to the next owner if they decide to sell the property or lose the rebate. This protects the tenant but is a barrier for landlords.

I learned that a direct remedy could take the form of a municipal bylaw, provincial legislation, or an administrative board. Indirect remedies like energy labelling and banning oil in rental housing could also help.

Landlords are not incentivized to include the tenant’s power in rent because of a lack of funding. A government subsidy could encourage landlords to pay for power, thus incentivizing energy efficient retrofits.

This internship provided me with more than knowledge about the legal climate of energy efficiency and housing. I got to facilitate a discussion at my first local conference. I gave an informational tour of the Ecology Action Centre office building to the Coady Institute. I made connections in spaces like Efficiency Nova Scotia and the Clean Energy and Equity Network.

And I worked with a supportive and fun team that made me feel like a part of their world, even if it was only for eight weeks. I came to work each day excited and inspired. Thank you, Energy Team, for allowing me to explore those professional and personal experiences with you.

Don’t Panic; Decarbonize

St. Andrew’s United in New Richmond, Quebec, is a small English church on the southern coast of the Gaspé Peninsula between the municipalities of Maria and Caplan. “We're a church that has been celebrating the 185th year of our building,” says Alice Campbell-Dell, the Chair of the Board of Trustee Stewards for the building.

"We’re aging and small—with 20 to 30 people in church on a given Sunday—but we are close, with deep historical ties and traditions. The actual congregation is bigger, but the average age is around 85, so we have many shut ins.”

St. Andrew’s United on the Gaspé Peninsula brings 185-year-old church building into the 21st century | Aug 20, 2024

For years the congregation has been contemplating how to become more carbon friendly, and the anniversary seemed just the occasion to take the plunge into energy retrofits and get rid of two old oil boilers that heated the church, replacing them with highly efficient heat pumps. “We were fortunate in that we received a legacy last fall from a former parishioner,” Campbell-Dell says.

There were simple instructions that came with the money: “Please do something that the church needs.” That was just the motivation needed to get started with an Expression of Interest for the Faithful Footprints funding program, which could cover up to $30,000 of the work.

In hindsight, that part was easy. “Applying for a Faithful Footprints grant is the easiest part,” says Campbell-Dell. “Churches should definitely get in touch. If for no other reason just to listen to Stephen Collette [Building Audit Manager]. He is so articulate and funny and it’s a pleasure to sit and listen to him for a while.

In hindsight, that part was easy. “Applying for a Faithful Footprints grant is the easiest part,” says Campbell-Dell. “Churches should definitely get in touch. If for no other reason just to listen to Stephen Collette [Building Audit Manager]. He is so articulate and funny and it’s a pleasure to sit and listen to him for a while.

“They cover two-thirds, which is very generous. But you also need to know your own assets, so you can cover the other third. There is tremendous moral and financial support from Faithful Footprints. They made it easy.”

Campbell-Dell says the paperwork was the most intimidating part of the process, but the accessible support from the Faithful Footprints staff made it easier. “Not painful at all,” says Campbell-Dell. They are still going through reporting requirements for a matching Hydro Quebec grant, but the work with Faithful Footprints has given them confidence they can do it.

The single biggest challenge for this rural congregation was finding craftsmen who could do the work and were available. “It’s an informal attitude to things, like paperwork,” she says. “That was our first hurdle. And working in French can complicate things.

“It’s been a journey but it’s been worth it.”

The heat pumps went in (and the oil boilers out) in spring, so they have yet to see how people will find the winter, or what the bills will be like. For now, people love the efficient cooling system heat pumps provide.

what the bills will be like. For now, people love the efficient cooling system heat pumps provide.

“It’s nice not to be sweltering in the summer,” Campbell-Dell says. “It used to be dangerously hot at events we’d hold. And we’re not pouring emissions into the atmosphere anymore.”

Church members, after some disagreement over acceptable room temperature, agreed to set the heat pumps at 22 and leave blankets in every pew for those who like it warmer.